Feature

The father of boy bands

Fifty years ago, bilingual nikkeijin Johnny Kitagawa came up with an unlikely idea that went on to redefine Japanese show business and make his agency a byword of boy band pop.

On the 50th anniversary of his all-powerful talent agency, ‘Janizu’ or Johnny’s & Associates (J&A), 81-year old Johnny (Hiromu) Kitagawa, the mysterious and reclusive boss of the most successful idol-producing agency in pop music history, can afford a smile from his $10m Shibuya mansion. In May 1962 when, this first generation Japanese-American first came up with the idea of forming a boys teenage pop group whose dance moves rather than vocal or musical talent would be their sales point, his contemporaries must have thought it the delusional notion of a rank outsider. Fifty years on, the dance idol model he created with his first boys group, The Johnnies, has not only become established across much of Asia, it is the only form that matters for a great many young fans. Indeed for much of young Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese youth today, the very idea of a pop group who cannot dance or act is a quaint one.

What then, did Johnny Kitagawa know or understand in 1962 that would allow him, two decades later, to build the most the most successful production and talent agency in popular music history, a fact acknowledged just two years ago by the Guinness Book of Records? The story of Johnny Kitagawa’s unique and controversial show business career begins in 1950 in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo. Kitagawa’s father had been sent by a Buddhist sect to administer to the LA Japanese community there and had married a first generation Japanese-American. In May 1950, his 18 year-old son Hiromu (Johnny), already a musical fan, was given the job of interpreting for 13 year-old Japanese kayokyoku (a J-pop sub-genre) singer Hibari Misori when she performed at the Hongwanji-affiliated Koyasan Hall on her California tour. This experience inspired him to join the US military as an interpreter and with the Korean war at its height, he soon obtained a position with the American embassy in Tokyo.

According to legend, some time in 1958, while working for the US embassy, Kitagawa began to spend time with teenage boys playing baseball in Yoyogi Park and formed an informal club named after him. The story then jumps to January 1962, when after taking some of the team to see a production of West Side Story, he first pondered the idea of a boys dancing group. This was in fact a pretty daring idea given that it was then considered quite unmanly for Japanese men to lift their legs while dancing. The four-member group The Johnnies, did achieve some success. By the mid-1960s, however, the Beatles and Ventures-inspired Group Sounds (Beatles-inspired J-pop genre) era had begun and college age boys playing their own electric guitars seemed poised to challenge the idol-singer template that had prevailed in Japan in the early 1960s.

Undiscouraged, Kitagawa now turned to a business model developed in the US by pop music entrepreneur, Don Kirshner, the man behind The Monkees. The latter’s TV show aimed at the low teen female demographic had achieved enormous success as an entertainment product built around mass marketing and advertising. Convinced that an idol-type group made up of dancing boys could achieve a similar kind of success, Kitagawa began promoting a new boys group called the Four Leaves. The group had several hits but failed to match the impact of The Monkees in the US or indeed that of female idols such as Momoe Yamaguchi and Pink Lady who dominated the Japanese music industry in the mid-1970s. J&E remained a relatively minor player in Japanese show business well into the late 1970s.

Given this relative failure, what made Kitagawa stick so unshakably to his belief that unthreatening adolescent dancing boys performing musical style numbers could attract a truly mass female audience? Some might suggest that his gay sensibility gave him an insight into the latent possibilities of the ‘boys love’ homoerotic phenomenon that was then emerging through shojo manga. Others have hinted that his motivation and drive were a product of his need to be surrounded by, and in total control of, easily replaceable pubescent boys who would do his every bidding. This theory has at least some credibility given later accusations — largely substantiated by a Tokyo Court in 2003 — of improper sexual relations with his charges. These explanations are certainly plausible but are they the whole story? It is equally plausible that Kitagawa had acquired an unusually insightful understanding of the dynamics and emotional subtext of Japanese school-based teen life. Is it possible that Kitagawa’s experience working with young teenage boys gave him insight into the powerful emotions that are unleashed in the bonding experiences of adolescents as part of the Japanese junior and senior high school experience? Did he recognize the importance of the human attachments and emotional ups and downs that are generated through club activities, with their calibrated sempai-kohai relationships? Perhaps it was this understanding that gave him the idea in the early 1970s of the so-called ‘Johnny’s Juniors’ system. Under this arrangement, J&E recruited boys into a talent pool, housed them in a dormitory and trained them over a period of years. The schools involve a formalized hierarchy among boys, so Johnny’s Juniors were, and still are, expected to interact with older boys (their sempai) and patiently persevere with their singing, dancing and acting skills before making their debut as backup dancers for the older members. Some might draw parallels with the sumo stable system and the Japanese apprenticeship tradition. Either way it seems likely that Kitagawa’s insights into the Japanese teenage psyche helped J&E to achieve unprecedented commercial success in the following decade.

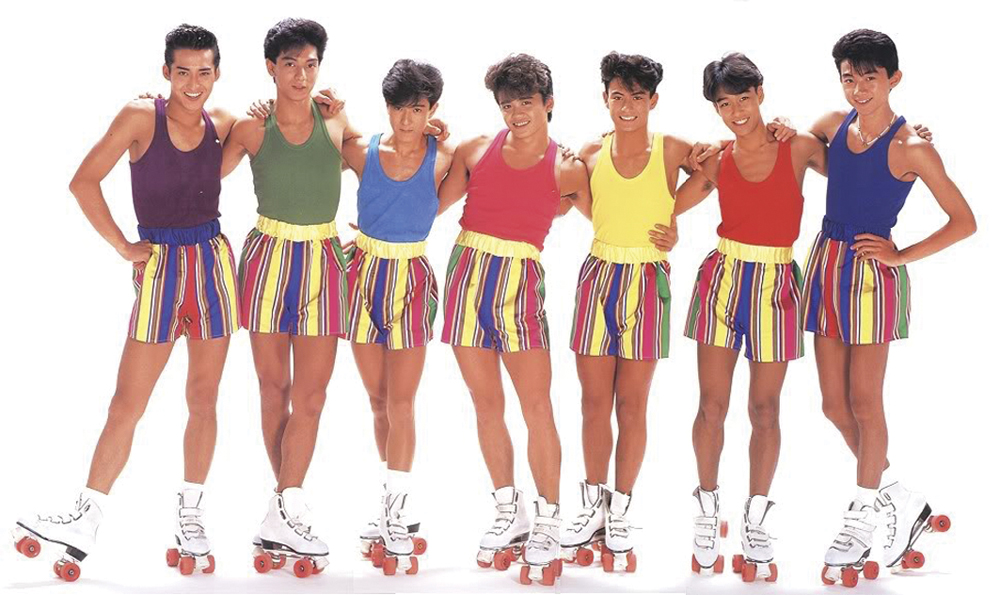

As any older J-pop fan knows, it was Hikaru Genji, J&E’s roller-skating flagship group that would launch ‘Janizu’, as it was now called by its fans, into the upper realms of show business during the 1980s. By the time the group made its debut in 1987, J&E had also begun to use his increasing clout to place members of his groups into TV dramas and comedies. While such a concept seems unremarkable in today’s Japan, the idea that pop stars could routinely function as credible actors or comedic hosts of variety TV programs, is one that was (and still is) quite unimaginable in any western entertainment market where acting talent is seen as a entirely unrelated to musical proficiency.

The story of J&E after Hikaru Genji has been told many times and hardly needs retelling. It includes the extraordinary success of SMAP, the ultimate entertainers; Arashi, the definitive all round boys group and TOKIO, the ‘rocker’ older brother outfit. More recent groups include Kat-Tun and this year’s updated Hikaru Genji. Many of these accounts have focused on the aforementioned sex scandals as well as the agency’s ruthless tactics dealing with TV outlets that do not give priority to J&E stars when choosing performers for their teen-oriented features. Yet whatever one’s opinion of his highly profitable, tightly run empire in which catering to the teen demographic is the first priority, no one can question the extraordinarily high level of sheer professionalism and endurance that Kitagawa’s protégés display. On a daily basis, these idols not only follow a rigorous practice schedule but assume multiple and ever changing roles and functions across the entire spectrum of the entertainment world. If there are doubts about the work ethic of today’s young Japanese, they need only look at the daily routine that J&E’s highly disciplined and multi-talented units follow in order to cater to their adoring fans, often at great personal cost. Marriage for example has until recently, been highly discouraged. Moreover, Janizu groups were among the most frequent visitors to the Tohoku area after the 2011 tsunami. Whatever one might think of the musical and cultural legacy of Johnny Kitagawa, if enriching the lives of millions of otherwise bored junior high school girls across three generations is one of the legacies of his fifty years, then the reclusive 81 year-old workaholic surely deserves a day or two off.