Feature

Sake Sensei’s Brewery Adventures

In the second part of our exploration into the world of sake, we take a closer look at the brewing process itself—a labor-intensive process requiring keen attention to detail. So, just how is it made?

Illustration: Tim Wilkinson

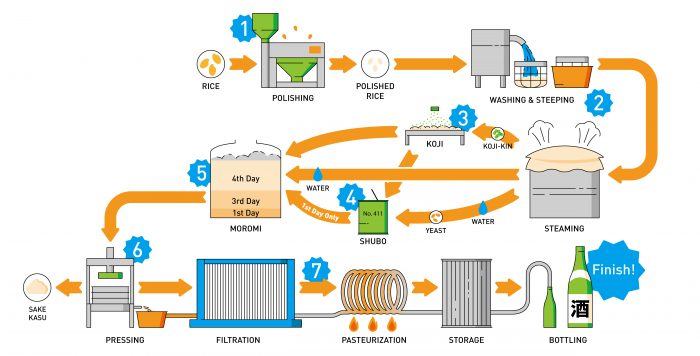

The Sake Brewing Process

1.Polishing

Premium rice, invariably the Yamada Nishiki variety, is first polished incredibly slowly (sometimes for as long as 50–60 hours) in industrial milling machines to remove the husks, proteins, and other impurities that may adversely affect the taste. The degree to which it is polished varies between 30–60% of the kernel remaining, depending on the type of sake to be brewed.

2. Washing, steeping and steaming

The milled white rice is carefully washed by hand and allowed to steep before being steamed. The amount of time it is left to soak up water depends on the extent to which it has been polished in the first step. Highly milled rice may only need a few minutes to steep, whereas less polished rice may require several hours or to be left overnight. It is all precisely measured.

3. Making koji

Some of the steamed rice is then used to create koji—rice that has been cultivated with special mold spores called aspergillus oryzae. The koji is left to incubate in temperature- and humidity-controlled rooms (koji muro) from 36–72 hours in stacks of linen-covered trays. The koji is continuously monitored and mixed by hand at regular intervals with clinical efficiency.

4. Preparing the yeast starter—the shubo

The finished koji, steamed rice, and water are combined in small vats, and liquid yeast is added. The temperature of this mini mash is controlled by inserting metal vessels filled with either hot or cold water as required for optimum fermentation. The shubo is left to bubble away for up to two weeks.

5. The mash—moromi

The shubo is then moved to larger tanks, and yet more rice, koji (from a different batch), and brewing water are added in three successive stages over a four-day period, a process known as sandan shikomi. Once completed, the mash will be left to work its magic. The koji will convert the starch in the rice into glucose, which the yeast will then use to create alcohol and carbon dioxide. The conversion of starch to sugar and sugar to alcohol takes place in parallel, all in the same tank. This is known as “multiple parallel fermentation,” and is a process that is unique to sake brewing.

6. Pressing

Once the moromi is completely fermented, the resulting sake is still a viscous gloop of ricey goodness, rather than a fine clear liquid. In order to produce clear sake, it must be passed through an industrial press to separate the sake lees—the solids, or sake kasu—from the liquid. Before being pressed, however, distilled alcohol may be added to the moromi to draw more flavor and aroma compounds from the lees. The amount of distilled alcohol added (if any at all) depends on the type of sake being produced. Sake with no additional alcohol added is called junmai sake. The sake lees make up about 25% of the moromi and the excess sake kasu is often used as a nutritional cooking ingredient, so nothing goes to waste.

7. Filtration and pasteurization

The sake is then filtered, pasteurized, and placed in cold storage where it matures before being bottled. Sake that is unpasteurized is known as namazake, and has a sparkling freshness requiring it to be stored chilled.

Kansai Kura Closeup

Kirakucho 喜楽長

Mayuko Kita

Mayuko Kita oversees sake production at this 200-year-old kura (sake brewery) in rural Shiga, under the watchful eye of her father. She is one of only a handful of female sake brewers in the country and, at just 28 years old, is part of a passionate and youthful movement dedicated to promoting sake to a new generation.

As well as traveling to sake conventions around the world, she collaborates with other young sake makers to release limited-edition brews, and earlier this year, even published a book that introduces the drink to beginners. The pride she takes in her trade is evident, as is the quality of the sake Kirakucho produces. Such is her dedication that she even sleeps in the same dorms above the mash tanks as her brewers during the winter brewing season.

Mayuko is keen to get her hands dirty with all aspects of the business, even designing the striking red-and-black labels for their flagship products herself. She believes that sake itself doesn’t need to change, but that efforts in marketing and awareness campaigns for sake generally can help change the public’s perception of what sake is, who it is for, and how to enjoy it. “What is good for the industry, can only be good for Kirakucho too,” she says.

Address: Shiga-ken, Higashiomi-shi, Ikeda-cho 1129

Tel: 0748-22-2505

kirakucho.jp

Sensei says

One of the most well-known breweries in Shiga, Kirakucho continues to be a leading light in the renaissance of sake across the region. Like many Shiga breweries, it started out just selling basic sake to the local community—brewing its best stock for Gekkeikan in Kyoto. As the sake market waned, however, they were forced to reassess and began producing premium lines under their own brand, thus forging a path for others to follow.

Sensei Selection

|

1. Daiginjo (大吟醸) Highly aromatic and pairs well with appetizers, including carpaccio and other Western dishes. |

|

2. Karakuchi Junmai Ginjo (辛口 純米吟醸) Sharp and dry, yet with a sweetness derived from the koji, this sake goes well with sashimi. |

|

3. Tokujun (特純) A robust sake that pairs well with izakaya foods and other bolder dishes. |

|

4. Junmai Daiginjo (純米大吟醸) A premium sake that pairs well with steak and other red meat. |

|

5. Junmai Daiginjo Itoushi (愛おし) A delicate dryness that perfectly offsets sweeter dishes and stews. |